Recently I was forced to cancel a spring workshop due to low enrollment. And by low, I’m talking zero enrollment, as in not one person signed up. Nada. Zilch. It’s a first for me. Sure, I’ve had less than full workshops, but never one with zero interest. I’m left to wonder, what the hell happened?! Am I no longer loved (perish the thought!)? Is it time to dump the workshop for a new one? Whatever the reason(s), I won’t deny feeling the bitter sting of rejection. How could I not? (Before I proceed further, please know that I am not attempting to foster sympathy or solicit support of any kind. As with much of my writing, I am sharing an experience in the hope that you will find it interesting and/or enlightening).

Fortunately, rejection is nothing new to me. Dealing with rejection is part and parcel of the life of any artist. There are far more failures than successes. Still, it never gets easier, and this one particularly hurts. The only thing to do is take the blow, learn from it, and move on. I’ve been down this road before, I’ll survive. You’ll get no whining from me. Well, at least not publicly. Privately I pound my pillow at night with my fist, asking why me, why?! However, rejection is not what is on my mind today.

It’s moments like these when I consider the choices I have made. While canceling a workshop may be a blow to my ego, its greater impact is on the bottom line. As a professional photographer, workshops are one of my primary sources of income. Without a doubt, the single greatest source of anxiety and stress with being a professional is making enough money to support the lifestyle. I sometimes feel like a huckster, endlessly devising ways to make a buck. Too often it distracts me from the far more important and joyful task of creating photographs.

When I discovered a passion for photography, it was my dream to make it my vocation. It took 22 years, but I got there. And yet, I often find myself asking, am I content? It certainly isn’t all that I imagined it to be. I couldn’t have known the negative aspects of being a full-time photographer beforehand. Or perhaps I was too naive to see them. Things in life are rarely what we imagine them to be, and being a professional photographer is a prime example. Becoming a professional meant I had to make money in photography. Who knew??

Sometimes I find myself putting on the proverbial rose-colored glasses and thinking about my life before I turned “professional.” For over ten years I worked part-time as a consultant in my previous career, a position that afforded me a greater albeit unstable income while simultaneously allowing me the freedom and flexibility to pursue my photography. The best of both worlds, right? Except that it wasn’t. I was too comfortable. I wanted to do more with my photography, but I lacked incentive. I wasn’t hungry enough. As sometimes happens in life, the decision to pursue photography full-time was made for me when the work dried up. That’s a good thing, sometimes we need a kick in the butt to get us going.

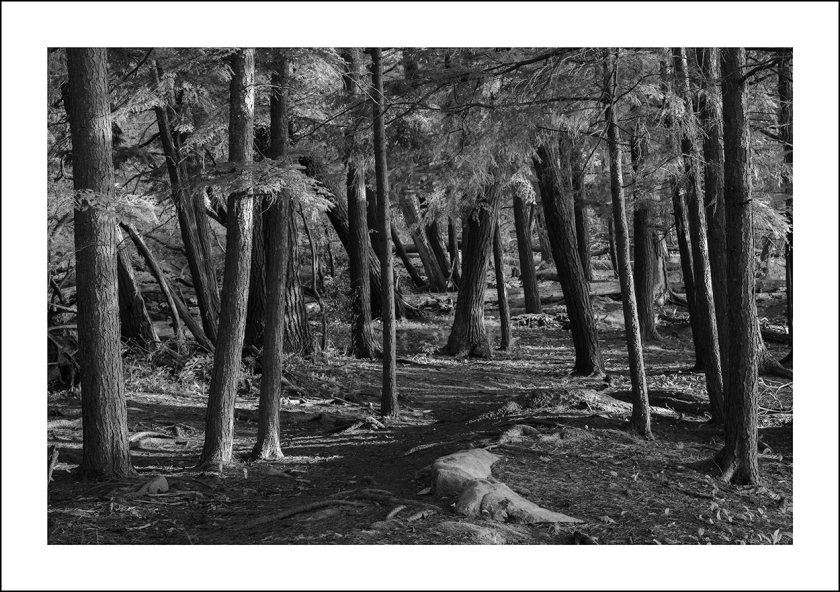

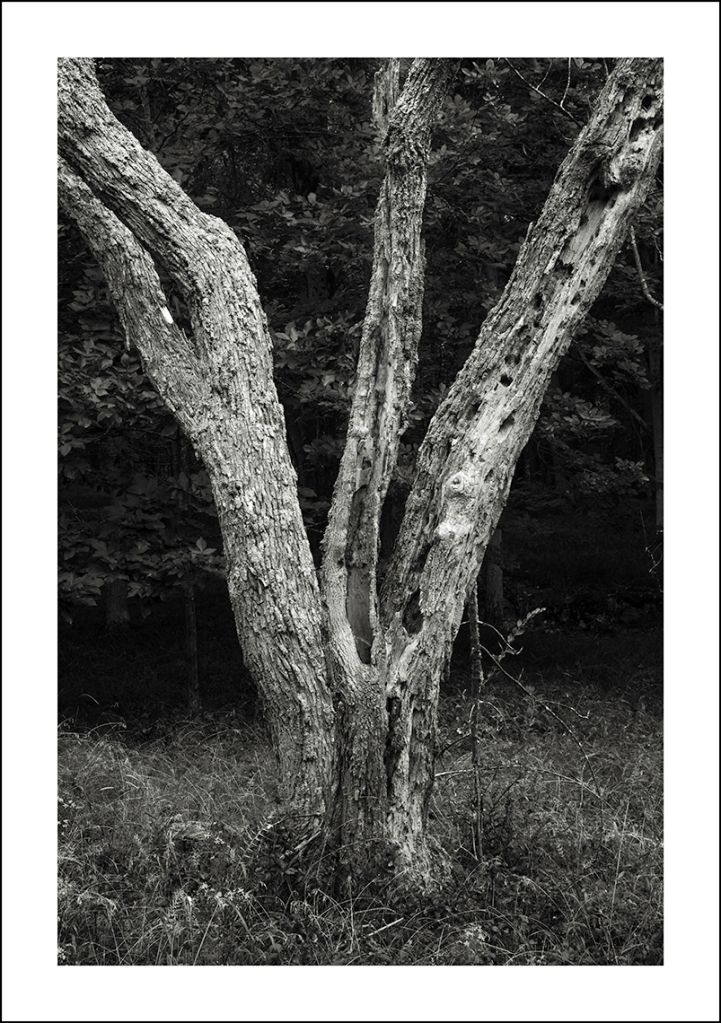

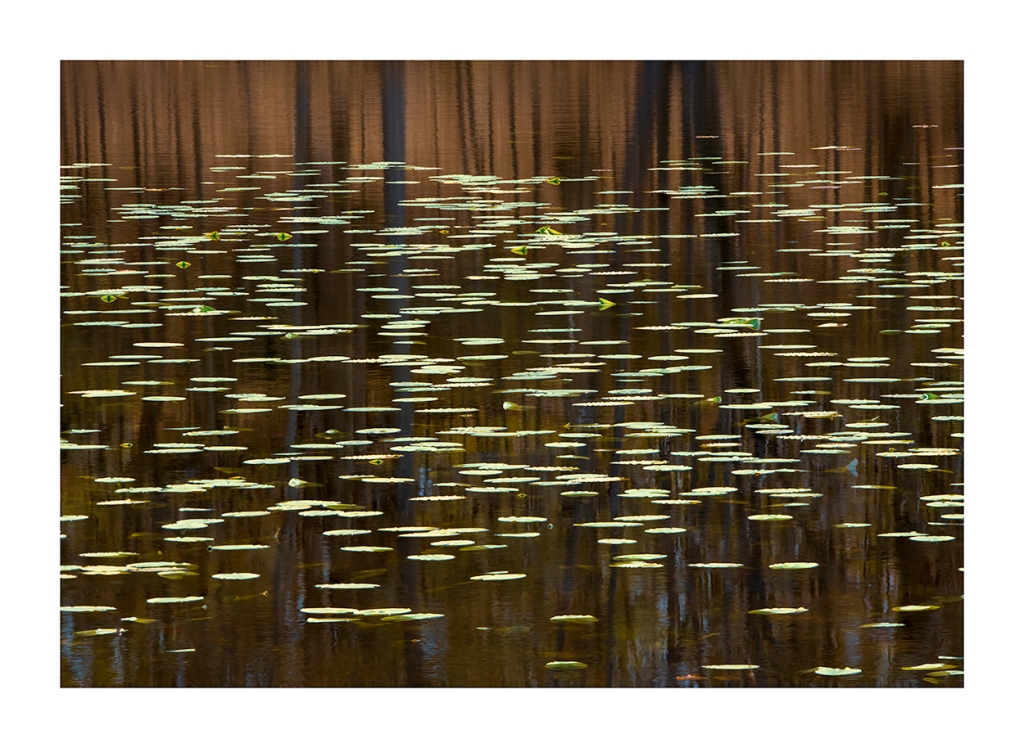

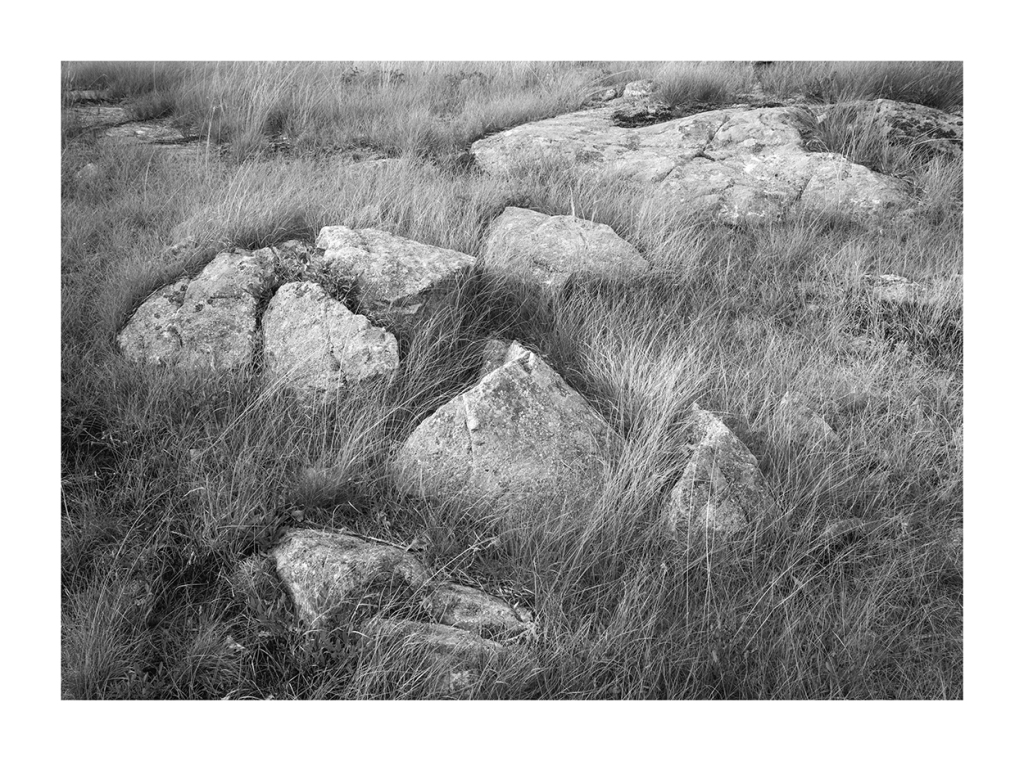

I have been a full-time photographer now for seven years. It can be a grind at times, inventing new workshops, creating presentations, and thinking of topics to write about. All of which amounts to nothing if not marketed well, the most hated task of every photographer, living or dead. And none of it carries with it the guarantee of financial reward. Further making matters more difficult was the decision to make only personally creative and expressive photos, commonly referred to as fine art photography. In other words, the kind few people want to purchase. Who doesn’t want a black-and-white picture of tree roots on their wall?

Living the life of a full-time photographer has required sacrificing security for the freedom to spend my days on creative pursuits. Having tasted that freedom I can never go back. More important, however, is that I am leading an authentic life. As a geologist, I felt like an imposter. I was well compensated, but leading a false life. Warts and all, this is the life I have chosen, the life I need to lead. In the grand scheme, a canceled workshop won’t amount to much. The only thing to do is keep moving forward. Perseverance, not talent is what separates the successful from the unsuccessful.